Intimism in Painting

BETWEEN SILENCE AND NOSTALGIA

José Hierro

A native of Santander and Californian by birth, Adolfo Estrada first discovered his painting and later the painting. He painted and drew following this interior need akin to those who believe that the creative act serves to give testimony of him. He painted and drew maybe without knowing that such an activity had to do with what we call Fine Arts. One day, he became acquainted with the painting of the young masters of the forties: Alvaro Delgado, Pedro Bueno, Martínez Bull, García Ochoa...I suppose that the formal distortions, the aggressiveness of color of some of them would fill him with astonishment. All this happened in the days in which Proel, the poetical magazine and art venue, was initiating the task of updating the inhabitants of Santander on issues of the arts. I suppose that Adolfo Estrada would be very surprised by the aesthetics of, for example, Aguayo, Lagunas and the members of the “zaragozano Pórtico”. Or by Tàpies in his stage of magic priest of the “Dau al Set”, as well as, by Willy Baumeister and Carla Prina. His artistic apprenticeship consisted of the contemplation of the works of these and other contemporary painters as well as the publicity drawings that were his “modus vivendi” at that time.

Other works, he took from the highland landscape of Cantabria, from the silver shine of the bay, from the whitish light, like that of water with anise beading through the windowpanes, lightly moistening a few objects placed on a table. A colorless light, which extinguishes the stridencies of the contrasting tones and at the same time, enriches the hues.

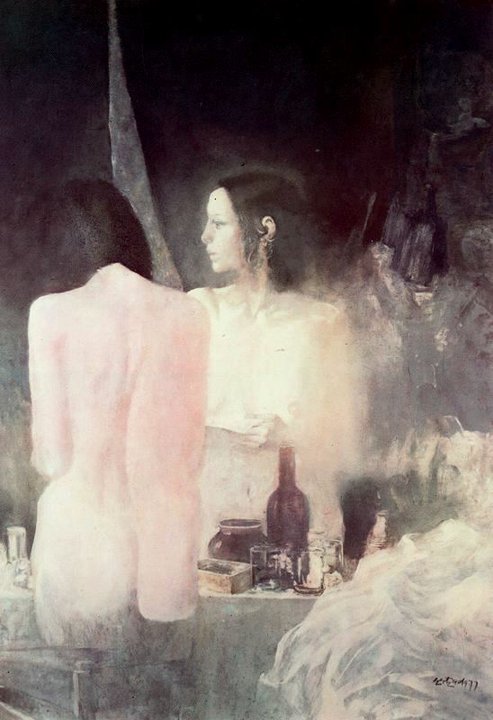

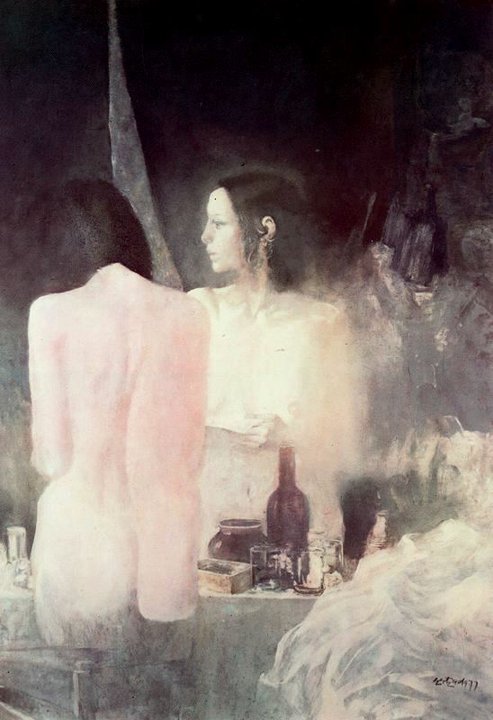

Adolfo Estrada, as so many other painters of our time, is of self-taught formation. His studies at the School of Fine Arts were brief and informal. But unlike the majority of the self-taught, he did not replace the knowledge of craft with novelty. He was a self-taught painter who did not deny tradition, but sought it at his own risk. As an artist, he granted the plastic fact all its independence. He felt that the essential in art is not the “what” but the “how”. But the “what” of his pictures was always the essence of a substantial piece of reality: still lives, especially in his earlier wanderings. Later, the feminine figure became his fundamental topic. Parallel to the change of subject matter, the gradual transformation of the palette: earthy, reddish-sienna and brown shades - initially; silvered now. Increasingly more refined, exquisite and elegant, without the minor ostentation – new-wealth - of the matter.

(There is in Adolfo Estrada's painting something that makes me think about Bécquer. It is perhaps this process of idealization to which he submits the reality. The objects, the feminine figures turn out to be air, immaterial, as if dreamt, moved to a metaphysical area. Regarding this vision, "Intangible" figures come to mind, as the ideal woman of the Sevillian poet. The parallel can be extended also in the field of the expression. In Bécquer, the word turns out to be dispelled, submitted to the verse which in turn is submitted to the poem, without a metaphor that surprises, without an image that dazzles.)

Maybe the recollection of Bécquer is motivated by what in the painting of Estrada exists of romanticism. Would be said an artist who portrays the spectra of the prominent characters of Esquivel. He portrays the models of Esquivel from the other side of the mirror, from the invisible dimension, from the area where time does not exist. It is a painting of metaphysical spaces. When he thinks he is painting the reality, he is painting the unreality within.

It is possible that all this turns out to be excessively digressing and literary. In particular, explaining a process that for the artist is much simpler. Perhaps it is preferable to say, simply, that Adolfo Estrada is an intimist painter. He paints the things as if he remembered them with love. In the way between the contemplation and the recollection, the models - things or beings - have lost its naturalistic precision, the details and qualities that are consubstantial, which would grant them, if they were to be reproduced faithfully, their total veracity. But on having lost truth they have gained poetry. They have departed the area of nature to enter that of the painting. They have become ideal creatures. All this happens because the artist paints them not as they were when he contemplated them, but as they have to be in the kingdom of painting. He reconstructs them stepwise, shade by shade. He guesses them in the semidarkness, and fixes them with tiny touches of paintbrush, with subtle effects of blur, advancing towards the kingdom of the most radiant white, but without entering, remaining in the ivory, in the grayish pearl, in the ashes. The motives of his painting give us the impression - of proustian nature - that have always belonged to the daily world of the artist, but in the process of recreating them, the conscious memory and the unconscious one have adorned them, turning them into a new, different product, though, nevertheless, still loyal to the deep truth of the models.

To paint the recollection of the things is to enter time, to travel towards the past. And this trip cannot be done without the irreplaceable guide: melancholy. This is the chord on which relies Adolfo Estrada's art (like also that of the Bécquer of the "rhymes", at least those that do not turn out to be corroded by the acid of sarcasm), which gives the general tone to his plastic inventions, which distinguishes him and turns him

into an island surrounded by these dramatic, coldly rational waters or bursting lucid ones that constitute the ocean of Spanish contemporary art.

In short, Adolfo Estrada’s painting is between silence and nostalgia. To be watched from the loneliness, as if windows opened to the lost time. Without thinking that these dreamed, dull images, have been rescued thanks to a skill of beauties and infinite subtleties; thanks to a rich matter that seems to want to forgive its richness, and so it hides it, and tries to pass unnoticed at the first sight. Pure as the painter’s painting that wants to appear as a sentimental impulse, like "Germanic little rustles” ", as the work of a poet who recovers the spirit of the lost things.

( Guadalimar, Madrid, January, 1978)

BETWEEN SILENCE AND NOSTALGIA

José Hierro

A native of Santander and Californian by birth, Adolfo Estrada first discovered his painting and later the painting. He painted and drew following this interior need akin to those who believe that the creative act serves to give testimony of him. He painted and drew maybe without knowing that such an activity had to do with what we call Fine Arts. One day, he became acquainted with the painting of the young masters of the forties: Alvaro Delgado, Pedro Bueno, Martínez Bull, García Ochoa...I suppose that the formal distortions, the aggressiveness of color of some of them would fill him with astonishment. All this happened in the days in which Proel, the poetical magazine and art venue, was initiating the task of updating the inhabitants of Santander on issues of the arts. I suppose that Adolfo Estrada would be very surprised by the aesthetics of, for example, Aguayo, Lagunas and the members of the “zaragozano Pórtico”. Or by Tàpies in his stage of magic priest of the “Dau al Set”, as well as, by Willy Baumeister and Carla Prina. His artistic apprenticeship consisted of the contemplation of the works of these and other contemporary painters as well as the publicity drawings that were his “modus vivendi” at that time.

Other works, he took from the highland landscape of Cantabria, from the silver shine of the bay, from the whitish light, like that of water with anise beading through the windowpanes, lightly moistening a few objects placed on a table. A colorless light, which extinguishes the stridencies of the contrasting tones and at the same time, enriches the hues.

Adolfo Estrada, as so many other painters of our time, is of self-taught formation. His studies at the School of Fine Arts were brief and informal. But unlike the majority of the self-taught, he did not replace the knowledge of craft with novelty. He was a self-taught painter who did not deny tradition, but sought it at his own risk. As an artist, he granted the plastic fact all its independence. He felt that the essential in art is not the “what” but the “how”. But the “what” of his pictures was always the essence of a substantial piece of reality: still lives, especially in his earlier wanderings. Later, the feminine figure became his fundamental topic. Parallel to the change of subject matter, the gradual transformation of the palette: earthy, reddish-sienna and brown shades - initially; silvered now. Increasingly more refined, exquisite and elegant, without the minor ostentation – new-wealth - of the matter.

(There is in Adolfo Estrada's painting something that makes me think about Bécquer. It is perhaps this process of idealization to which he submits the reality. The objects, the feminine figures turn out to be air, immaterial, as if dreamt, moved to a metaphysical area. Regarding this vision, "Intangible" figures come to mind, as the ideal woman of the Sevillian poet. The parallel can be extended also in the field of the expression. In Bécquer, the word turns out to be dispelled, submitted to the verse which in turn is submitted to the poem, without a metaphor that surprises, without an image that dazzles.)

Maybe the recollection of Bécquer is motivated by what in the painting of Estrada exists of romanticism. Would be said an artist who portrays the spectra of the prominent characters of Esquivel. He portrays the models of Esquivel from the other side of the mirror, from the invisible dimension, from the area where time does not exist. It is a painting of metaphysical spaces. When he thinks he is painting the reality, he is painting the unreality within.

It is possible that all this turns out to be excessively digressing and literary. In particular, explaining a process that for the artist is much simpler. Perhaps it is preferable to say, simply, that Adolfo Estrada is an intimist painter. He paints the things as if he remembered them with love. In the way between the contemplation and the recollection, the models - things or beings - have lost its naturalistic precision, the details and qualities that are consubstantial, which would grant them, if they were to be reproduced faithfully, their total veracity. But on having lost truth they have gained poetry. They have departed the area of nature to enter that of the painting. They have become ideal creatures. All this happens because the artist paints them not as they were when he contemplated them, but as they have to be in the kingdom of painting. He reconstructs them stepwise, shade by shade. He guesses them in the semidarkness, and fixes them with tiny touches of paintbrush, with subtle effects of blur, advancing towards the kingdom of the most radiant white, but without entering, remaining in the ivory, in the grayish pearl, in the ashes. The motives of his painting give us the impression - of proustian nature - that have always belonged to the daily world of the artist, but in the process of recreating them, the conscious memory and the unconscious one have adorned them, turning them into a new, different product, though, nevertheless, still loyal to the deep truth of the models.

To paint the recollection of the things is to enter time, to travel towards the past. And this trip cannot be done without the irreplaceable guide: melancholy. This is the chord on which relies Adolfo Estrada's art (like also that of the Bécquer of the "rhymes", at least those that do not turn out to be corroded by the acid of sarcasm), which gives the general tone to his plastic inventions, which distinguishes him and turns him

into an island surrounded by these dramatic, coldly rational waters or bursting lucid ones that constitute the ocean of Spanish contemporary art.

In short, Adolfo Estrada’s painting is between silence and nostalgia. To be watched from the loneliness, as if windows opened to the lost time. Without thinking that these dreamed, dull images, have been rescued thanks to a skill of beauties and infinite subtleties; thanks to a rich matter that seems to want to forgive its richness, and so it hides it, and tries to pass unnoticed at the first sight. Pure as the painter’s painting that wants to appear as a sentimental impulse, like "Germanic little rustles” ", as the work of a poet who recovers the spirit of the lost things.

( Guadalimar, Madrid, January, 1978)

source